Altitude sickness: Tips and Prevention

Altitude sickness, commonly known as soloche, is a common problem among tourists visiting Cusco and the Inca Trail. The beauty and history of these areas are due to a significant altitude, which can be a physical challenge for those who are not accustomed to these environments. In this blog we will explain altitude sickness, learn about its symptoms, how to prevent it and what to do if you suffer from it during your trip.

What is altitude sickness?

Altitude sickness, also known as acute mountain sickness (AMS), occurs when your body doesn't adjust well to reduced oxygen levels at high elevations. As you ascend to higher altitudes, air pressure decreases and oxygen becomes scarcer, forcing your body to work harder to get the oxygen it needs.

In response, your breathing rate increases and your body goes through several physiological changes. But if you ascend too quickly or don’t allow enough time to adapt, these adjustments can fall short—leading to symptoms of altitude sickness. Most people begin to experience symptoms above 2,500 to 3,000 meters (8,200 to 9,800 feet).

Main cause: At higher altitudes, there is less oxygen in the air, so the body has to work harder to get oxygen to the organs and tissues. This can cause physical stress, especially for those arriving in a hurry from a lower altitude.

Risk factors: Anyone can develop altitude sickness, but factors that increase risk include sudden arrival at high altitude, dehydration, excessive physical activity, and personal predispositions.

Symptoms of altitude sickness

Altitude sickness can range from mild to severe. Recognizing the symptoms is important for proper treatment:

Mild:

- Headache.

- Lack of energy or feeling tired.

- Dizziness and nausea.

- Anorexia.

- Insomnia.

Moderate:

- Vomiting.

- I feel as if my chest is being squeezed.

- My heart beats fast.

Severe:

- Difficulty breathing even at rest.

- Mental confusion.

- Cyanosis (bluish discoloration of lips and fingernails).

In severe cases, cerebral or pulmonary edema may occur, requiring immediate medical attention.

You might also want to check out: Best restaurants in Cusco | Top 20

Who is at risk of altitude sickness?

Anyone can experience altitude sickness regardless of fitness level, age, or experience. While some people are more vulnerable than others, understanding your personal risk factors can help you prepare better and prevent complications before they arise.

Risk factors: age, fitness level, and previous exposure

Altitude sickness doesn’t just affect people who are unfit or inexperienced. Rapid ascent, lack of acclimatization, and individual sensitivity are the main risk factors. Even healthy, athletic individuals can get sick if they go too high, too fast. People with a history of altitude sickness are more likely to experience it again.

Why even healthy people can experience symptoms

Being physically fit doesn’t make you immune. Altitude sickness is caused by reduced oxygen—not by poor conditioning. In fact, fit travelers often push themselves more, increasing their risk. Even trained hikers and athletes have developed symptoms on high-altitude treks.

High-risk destinations around the world

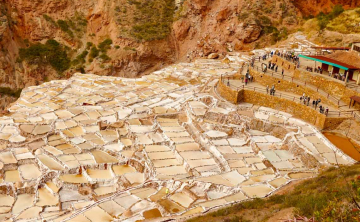

Many iconic travel spots are located at high altitude. Cities like Cusco, La Paz, and Lhasa, or trekking areas like the Everest Base Camp and Kilimanjaro, are well above 2,500 meters—the threshold where symptoms often begin. Travelers flying directly into these places are especially at risk due to sudden altitude exposure.

Preventing altitude sickness

Preventing altitude sickness starts with smart planning. Begin by designing an itinerary that allows for gradual ascent. Avoid flying or driving directly to high-altitude destinations without time to adjust. If possible, include stopovers at mid-altitude cities.

Some travelers take preventive medication like acetazolamide (Diamox) to help their bodies acclimatize more efficiently. Always consult with a healthcare provider before using such medication.

Training your body through light cardio, staying hydrated, and getting good rest before your trip also contributes to better adaptation. Remember: preparation is the first step to prevention.

The best way to enjoy Cusco and the Inca Trail without altitude sickness affecting your experience is to prevent it. Here are some essential tips:

- Acclimatize: Plan to spend at least two days in Cusco before starting the Inca Trail. This allows your body to gradually adjust to the altitude.

- Hydrate: Drink plenty of water to stay hydrated, as dehydration can worsen the symptoms of soroche.

- Avoid alcohol and heavy meals: These substances can make it difficult for your body to adapt to altitude.

- Consume coca leaves or coca tea: Coca leaves, traditionally used in the Andes, help alleviate mild symptoms of altitude sickness. You can chew them or prepare them as an infusion.

- Preventive medication: Consult your doctor before traveling about medications such as acetazolamide, which can help prevent altitude sickness.

- Climb gradually: During the Inca Trail, move at a slow pace and avoid excessive physical exertion in the first few days.

How to prevent altitude sickness during your trip

Once you're at high elevation, take things slow. Avoid gaining more than 300–500 meters (1,000–1,600 feet) in sleeping altitude per day once above 3,000 meters. Build in rest days into your itinerary every 2–3 days or after significant altitude gain. Drink plenty of water, eat a high-carb diet, and stay away from alcohol and heavy exertion for the first couple of days. Light activity is okay, but intense exercise should wait until you’re fully acclimatized.

One key strategy is to "climb high, sleep low"—hike to higher altitudes during the day but return to a lower altitude to sleep. And most importantly, listen to your body. Don't push through symptoms, as doing so could lead to dangerous complications.

What to do if you experience altitude sickness

If symptoms arise, stop ascending immediately. Rest and stay at the current elevation until symptoms improve. Mild cases usually resolve within 24–48 hours with rest, fluids, and light activity. If symptoms persist or worsen, descend to a lower altitude—this is the most effective treatment.

For severe cases like HAPE or HACE, seek emergency medical attention and consider using supplemental oxygen or a portable hyperbaric chamber if available. Medications like dexamethasone (for cerebral symptoms) and nifedipine (for pulmonary edema) are used in serious cases but should only be taken under medical supervision.

What should I do if I suffer from altitude sickness?

If you begin to feel symptoms of altitude sickness, follow these recommendations to minimize its effects:

- Rest: Stop and wait until your body has recovered before continuing.

- Stay hydrated: Be sure to drink plenty of fluids, such as water or hot tea.

- Supplemental oxygen: Some travel agencies provide portable oxygen for emergencies.

- Descent: If symptoms are severe, descend to a lower altitude as quickly as possible.

You might also want to check out: History of Cusco Peru: The imperial city that merges history

How altitude sickness affects specific activities

Altitude sickness doesn’t just affect hikers or climbers. From tourists visiting high cities to families traveling with children or seniors, everyone needs to be aware of how high altitude impacts the body during different types of activities.

Hiking and trekking at high altitudes

Trekking is one of the most common situations where altitude sickness occurs. Long, multi-day hikes like the Inca Trail, Everest Base Camp, or Annapurna Circuit take travelers into elevations well above 3,000 meters, where oxygen levels drop significantly.

Trekkers are often at higher risk because the physical exertion of hiking combined with daily altitude gain puts stress on the body. Without proper acclimatization, this can lead to headaches, fatigue, nausea, and more severe symptoms. A slow and steady pace is essential. It’s important to plan acclimatization days, limit your altitude gain to 300–500 meters per day once above 2,500 meters, and follow the "climb high, sleep low" strategy whenever possible.

Even if you feel strong, resist the urge to push forward too quickly—altitude sickness can sneak up on even experienced hikers.

Visiting high cities like Cusco or La Paz

You don’t need to be hiking for altitude sickness to hit. Many travelers arrive directly by plane or bus to high cities like Cusco (3,400 m) or La Paz (3,650 m) without any time to adapt. The sudden exposure to lower oxygen levels can trigger symptoms within a few hours, especially if you're dehydrated or fatigued from travel.

Tourists often feel pressure to begin exploring right away—taking city tours, walking uphill streets, or even starting hikes on arrival day. But this can backfire. The best approach is to take the first 24–48 hours to rest, hydrate, eat lightly, and allow your body to adjust before engaging in more physical activity. Many tour operators in high-altitude cities recommend a full day of rest upon arrival to reduce the risk of AMS.

Traveling with children or elderly

physical Altitude can affect children and older adults differently. Children might not be able to clearly communicate symptoms like headache or nausea, while elderly travelers may already have underlying health conditions that make high-altitude exposure riskier.

This doesn’t mean they can’t travel at altitude—but you should plan carefully. Choose itineraries that ascend gradually, avoid flying directly to extreme elevations, and allow for extra rest. Pay attention to changes in behavior, appetite, or energy, and be ready to descend if symptoms arise.

It’s also advisable to speak with a healthcare provider before the trip, especially for older adults with respiratory or cardiovascular conditions. Oxygen saturation monitors can be helpful tools to track health in both age groups during high-altitude travel.

You might also want to check out: The Inca Culture History

Myths and facts about altitude sickness

There’s a lot of misinformation surrounding altitude sickness, and believing the wrong things can put travelers at serious risk. From miracle cures to who it affects, these myths can lead people to ignore symptoms or make poor decisions during their trip. By understanding the facts, you’ll be better prepared to prevent and respond to altitude-related issues effectively and safely.

Common misconceptions about altitude sickness

One of the most widespread myths is that altitude sickness only affects unfit or inactive people. This simply isn’t true. Many professional athletes and experienced hikers have experienced altitude sickness despite their high level of physical conditioning. Fitness may help with endurance, but it has little to do with how your body adjusts to low oxygen.

Another common misconception is that taking painkillers, coca tea, or herbal remedies can “cure” AMS (acute mountain sickness). While coca tea and painkillers may provide temporary relief for some symptoms like headache or fatigue, they do not treat the root cause—lack of proper acclimatization. Relying on these without taking real preventive measures can lead to dangerous outcomes if symptoms worsen.

Some travelers also believe that if they don’t feel symptoms right away, they’re safe. But altitude sickness can take 6 to 24 hours to develop after arrival, and sometimes symptoms emerge after additional altitude gain, not immediately. Feeling fine on day one doesn't guarantee you’ll stay symptom-free.

Finally, many think that going down just a little will help—but in serious cases like HAPE or HACE, you may need to descend significantly (often 500–1,000 meters or more) to see improvement.

Scientific facts every traveler should know

physical The most effective way to prevent altitude sickness is to ascend slowly and allow your body time to acclimate. Experts recommend increasing sleeping elevation by no more than 300–500 meters per day once above 2,500 meters, and taking rest days every few days during longer ascents.

Hydration is essential, but drinking more water alone won’t prevent altitude sickness. However, dehydration can make symptoms worse, so staying properly hydrated supports better acclimatization.

Prescription medications like acetazolamide (Diamox) can help your body adjust to altitude more quickly. It’s best taken a day or two before ascending and continued during the ascent. This is especially helpful for people with a history of AMS or those who must ascend quickly for itinerary reasons. Always consult a doctor before using these medications.

Supplemental oxygen and portable hyperbaric chambers are used in more serious or emergency situations, but should not be relied on as primary prevention methods. Ultimately, the only true “cure” for severe altitude sickness is descent. Going to a lower altitude is the fastest and most effective way to relieve symptoms and prevent life-threatening complications.

Interesting facts about altitude sickness in the Andes.

Altitude sickness is one of the most common concerns for travelers visiting the Andes, but there’s much more to it than just “shortness of breath.” Behind this condition lie unique physiological reactions, surprising risk factors, and fascinating adaptations developed by Andean communities over centuries. These interesting facts will help you understand the science, the myths, and the realities of experiencing high altitude in this part of the world.

Local adaptations:

Over generations, the inhabitants of Cusco and other Andean regions have made physiological adaptations, such as increasing the number of red blood cells that can process oxygen more efficiently. Developed.

Traditional Traditions:

Coca leaves have been used by Andean peoples for centuries in religious ceremonies, as well as to prevent altitude sickness.

Impact on extreme sports:

Altitude sickness also affects athletes attempting to break records at high altitudes, such as the snow-capped Ausangate near Cusco.

In Summary

Enjoy your trip but be careful.

Altitude sickness is a real problem for anyone visiting Cusco and the Inca Trail, but it is a manageable problem. With a little preparation and a conscious mindset, you can minimize your impact and fully enjoy the natural and cultural wonders of these countries. Remember to always listen to your body, follow the advice of local experts and respect the Andean traditions that make this trip a unique experience.